Acne vulgaris (AV) is an incredibly annoying chronic skin disease. Teenagers around the globe are tormented by it, although most grow over it. Nevertheless, it's quite common in adults too [1]. And if you've grown over it, you can still be struck by it when you start using anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS).

This article has gotten ridicliously long, so I've included a brief table of contents with clickable links here:

But what causes acne? Briefly, four primary factors have been found to contribute to the development of acne. These are (in no particular order) [2]:

- Sebum production by the sebaceous glands

- Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes) follicular colonization

- Alteration in the keratinization process

- Release of inflammatory mediators into the skin

So sebum production by the sebaceous glands is, usually, not an issue. It's what they're supposed to do. It starts to become a problem when sebum production gets too high. Which is, on it's own, still not particularly problematic. I mean, greasy skin isn't the same as acne. However, this leads to two additional problems. First, it provides a comfy environment for the bacteria P. acnes. Second, it might induce inflammation [3]. (And P. acnes is thought to contribute to inflammation as well [4].)

How do anabolic steroids tie into this? Androgens appear to be required for the production of sebum (and consequently the development of AV) [5]. Administration of testosterone to adult males has been found to increase sebum production [6]. Another trial found that sebum production in the forehead, but not on the nose or back, was related to testosterone dose (25 mg up to 600 mg testosterone enanthate weekly) [7]. However, the association wasn’t strong.

Besides the increased sebum production, so-called follicular hyperkeratinization also plays an important role. It’s basically a tongue twister to say that there are skin cells in the hair follicle behaving abnormally, becoming cohesive and shedding really fast. In particular, the skin cells (keratonicytes) lining the upper part of the hair follicle in the area where the pores of the sebaceous glands reside. These dead cells can stick around in the follicle (which they shouldn’t) and potentially block the pores of the sebaceous glands. There’s a bit more to the whole hyperkeratinization thing than this, but this is sufficient for a good understanding of it all. It is thought that androgens also affect this, although it’s not really clear how.

Anyways, so what happens when hyperkeratinization takes place is that something called a microcomedone is forming under your skin. You can view this as a little baby acne spot. It starts out very small, invisible at the surface of the skin. It’s the precursor to all acne lesions. It then keeps growing and growing as it fills up with sebum, bacteria, immune cells and the shed epithelial cells to become a comedone. Comedones come in two shapes, either closed (so-called whiteheads) or open (blackheads). These are about 1 to 2 millimeter in diameter. However, if you’re screwed, these guys just keep on growing, forming macrocomedones. It can rupture underneath the skin, leading to some full-blown inflammation. However, it can also grow at the surface of your skin, so you grow a big white greasy fella: a pustule. Because they’re at the top layer of your skin, busting these won’t give you scars. Nevertheless, you can be unlucky and have it growing in the deeper skin layers. You can recognize these by painful reddish bumps (papules). These twats can stick around for quite some time, hurt like hell, and can give rise to scarring because they’re embedded so deep in the skin. What seems to trigger all of the above seems to be inflammation, with subsequent hyperkeratinization as the second step. As noted earlier, inflammation can be caused by the increased sebum production. Additionally, P. acnes thrives under increased sebum production and further induces inflammation too. It does so by hydrolyzing triacylglycerols, thereby yielding free fatty acids which are thought to promote inflammation, as well as by production of some other molecule(s)

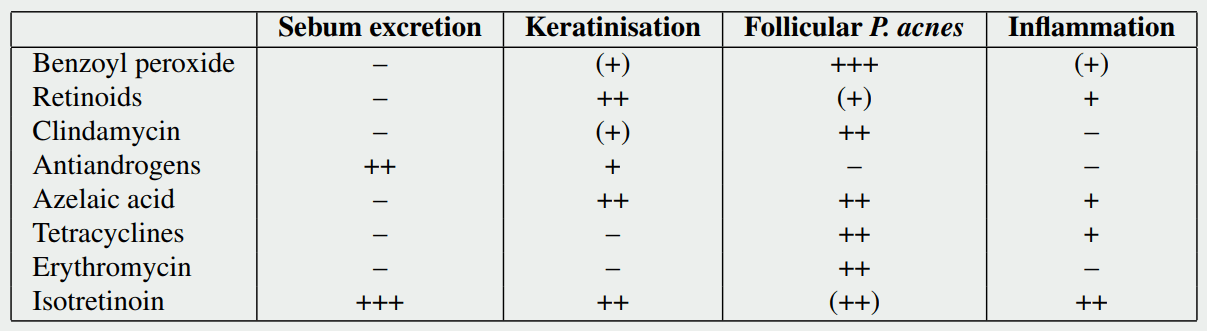

In light of this, treatment options which target sebum excretion and the keratinization process, are likely most effective in AAS-induced acne.

Treatment of acne by anabolic steroids

Treatment for acne can be subdivided into topical treatment and oral/systemic treatment. Topical treatment is simply putting stuff on the acne, acting locally. This can be time consuming if large areas of skin need to be treated. It should be noted in this regard, that they shouldn’t just be applied to the spots itself. It should be applied to the entire affected area, as it prevents acne development. Moreover, topical treatments can irritate the skin. And one common topical treatment (benzoyl peroxide) has a bleaching effect, making it difficult in use for areas which contact clothing (or towels, bed sheets, you name it, even your hair if you don’t watch out). Topical treatments can be effective and are the typical first line treatment. However, in some cases these are just plain impractical due to either the large skin area which you’d have to apply it to, or the location of the acne (it’s undoable to apply it to your back yourself). They can be split into three types: benzoyl peroxide, retinoids and antibiotics. I’ll cover each of them in subsequent subsections.

The oral treatments are usually initiated when topical treatments yield no or unsatisfactory results (with the exception of an oral contraceptive in women, which is often something to start with). These treatments have a systemic effect and thus treat the acne over the whole body. These can also be further subdivided into four types: antibiotics, nutraceuticals, hormonal or isotretinoin (Roaccutane). The latter is by far the most effective acne treatment, but has some nasty side-effects. All four will be covered in the subsequent subsections too.

It should be noted that face-washing and scrubbing likely does not reduce sebum production. It merely makes your skin dry by washing off the sebum at the surface of the skin. Besides that, it is also thought that scrubbing might even make things worse, as it might lead to rupture of comedones under the skin, leading to more inflammation. While there isn’t much or good research on this (I could only find one trial), it seems that face-washing should be limited to twice daily, as four times daily might also exacerbate it [8].

Finally, the following overview of treatments is far from an exhaustive overview of the literature. There is an enormeous amount of studies on these treatments discussed below and I could easily fill a book with them if I were to discuss them all and in sufficient detail. So what I’ve done is pick out the studies I feel are representative of the current state of literature and summarized them briefly.

Benzoyl peroxide (topical)

Benzoyl peroxide is commercially available as a topical treatment in a wide variety of concentrations spanning from 2.5 up to 20 %, with 5 % seemingly being the most commonly used. It has been around for ages and the first report I found about this was published in 1965 [9]. The efficacy of benzoyl peroxide can be ascribed to its potent oxidative capacity, generating free radicals. This makes it a very effective agent against P. acnes. Additionally, it also seems to display some keratolytic activity, and thus helps a bit in regard to the follicular keratinisation [10]. However, there's no evidence to suggest that it lowers sebum production. Yet it does tend to make the skin dry. Possibly also because of its oxidative capacity, as it will simply also oxidize the lipids and proteins on your skin.

Despite being the go-to first-line treatment for acne, strong evidence supporting its usage is lacking [11]. The trials are mainly plagued by unclear risks of bias, that is, certain methods simply have not been described in the papers. For example, good quality trials are randomized. Implying that subjects are randomly assigned to a treatment group (for example a placebo group vs a benzoyl peroxide group). Randomization ensures that each person has an equal chance of being assigned to either group. As such, indication bias and other forms of selection bias can be prevented and both groups will have a similar prognostic probability. So if something doesn't actually work (i.e. doesn't change the prognosis), you indeed won't find any differences between the groups after completion of the trial. However, it is important for research to describe their method of randomization. Sometimes randomization procedures are used which aren't really random at all, also called quasi random. When this isn't described, there is an unclear risk of selection bias. And as it happens, nearly all of the research on benzoyl peroxide hasn't described their randomization procedure. Similarly, other biases in this area of research are also unclear due to improper reporting of methods.

Anyways, although the research isn't of high quality, it is clear to suggest a positive treatment effect of benzoyl peroxide on acne. It's effectiveness seems comparable to that of oral antibiotics, as well as combination therapy of a topical antibiotic with benzoyl peroxide [11]. In fact, a problem with antibiotics is that it is thought that some strains of P. acnes have developed resistance to antibiotics to one degree or another, thereby limiting their efficacy [12]. Benzoyl peroxide is still very effective in such cases [13]. Till date, no strains resistant to benzoyl peroxide have been found.

Treatment should be started with application of a thin layer of benzoyl peroxide on the affected areas once daily. It seems wise to start with a 2.5 -- 5 % solution instead of a more concentrated one. In fact, research suggests the higher concentrations don't work better [14], yet they're bound to give more side-effects. After a couple of weeks visible progress should be clear. If not, you coud opt for twice daily application if side-effects allow it, or simply resort to a different treatment option.

Side-effects include dry skin, redness of the skin, irritation of the skin, pruritus (itching), and possibly on rare occasions contact dermatitis. Additionally, it makes your skin more prone to sunburn, so be sure to apply sunscreen appropriately on sunny days. It's advisable to switch from a once daily application to a once every other day application if side-effects are too pronounced.

Finally, I'd like to note that this treatment, while worth a try, tends to be not that effective in anabolic steroid-induced acne. The reason for this is probably because this treatment is especially effective against diminishing the P. acnes population, and to a lesser extent inflammation and keratinisation. However, as noted above, sebum production seems untouched. And the anabolic steroid-induced acne seems to mostly result from the increased sebum production.

Retinoids (topical)

While benzoyl peroxide is mainly effective against P. acnes, topical retinoids are mainly effective against keratinisation and to a lesser extent inflammation. The effectiveness against keratinisation effectively makes it comedolytic and anticomedogenic. It prevents the (micro)comedone formation, which is the precursor to all acne leasions as mentioned above.

Retinoids are molecules which bind to the same receptors to which vitamin A binds, namely, the retinoic acid receptors and retinoid X receptors. They can be viewed as derivatives of vitamin A, although they don't need to be structurally related. As long as they just bind and activate the same receptors as vitamin A does. In a sense, that makes retinoids acting in a hormone-like manner. They bind to these nuclear receptors which will modulate gene transcription, just like steroid hormones do for example. These receptors can then be further subdivided into different subtypes, which I'm not going to cover in this book. However, it's the reason why certain retinoids work slightly different from others. They simply bind and activate these subtypes to different degrees from one another. Within the scope of acne, these receptors regulate genes involved in the proliferation and differentiation of the cells lining the pilosebaceous unit. Or in more normal terms: they affect how these cells grow. Remember, the follicular keratinisation is in essence an abnormal behaviour of the skin cells, which makes them cohesive and shed fast. As a result, they don't normally shed on the skin surface. The retinoids hook into this by making them grow normal again in a sense. Similarly to benzoyl peroide, it does not seem to reduce sebum production. Notably, however, the oral retinoid isotretinoin (Roaccutane or Accutane) is extremely potent at reducing sebum production. (Discussed further down below.)

Several topical retinoids exist, such as tretinoin (probably the most commonly used), adapalene and tazarotene. And just like benzoyl peroxide, it also has been around for decades. The first publications dating back to 1962, with the use of tretinoin [15]. Several trials seem to suggest tretinoin works fairly well against mild-to-moderate acne. Reductions in total lesion count of 22 to 83 % have been reported [16]. Tretinoin is available at a wide variety of concentrations spanning from 0.01 to 0.1 %. Research found that 0.04 % tretinoin was similarly effective as 0.1 % tretinoin in reducing lesion count [17]. However, side-effects were similar between groups. (They used a microsphere formulation of tretinoin in this study, which improves it's tolerability while maintaining its effectiveness. It's unsure whether the same results would apply to regular 0.04 % and 0.1 % tretinoin creams though.) While visible results might take place within a couple of weeks, maximum improvement has been suggested to occur after 3--4 months [18].

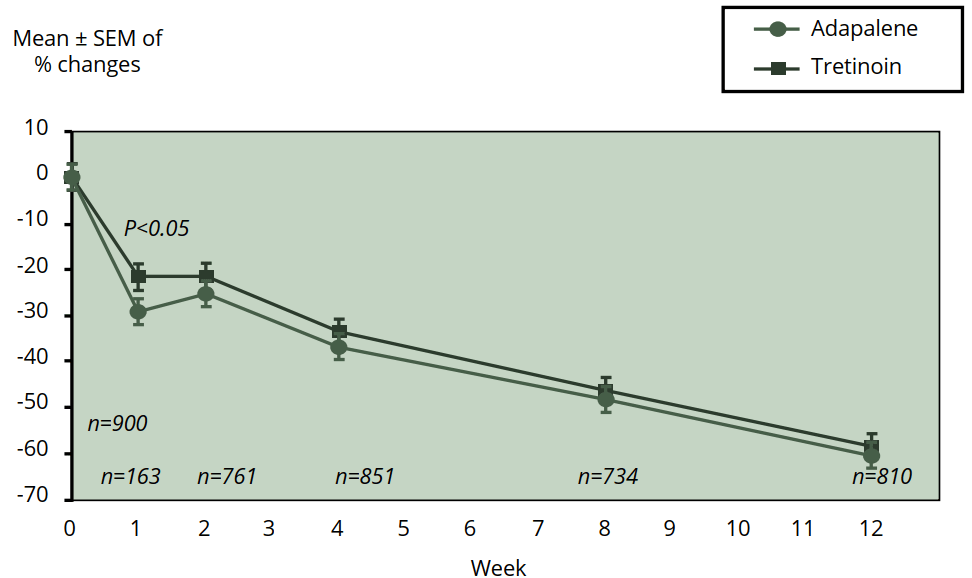

A relatively new retinoid is adapalene. It's available in concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 0.3 % and is better known under its brand name Differin. A meta-analysis of five studies was carried out to compare the efficacy of 0.1 % adapalene compared to 0.025 % tretinoin in the treatment of acne [19]. While ultimately tretinoin and adapalene were similarly effective at reducing acne lesions, adapalene got results faster. It already showed a significant difference in the reduction of inflammatory and total lesions at week 1 (see also the figure below). Moreover, the authors also note that the patients receiving adapalene demonstrated greater local tolerability during treatment. The 0.3 % adapalene also works better than 0.1 % [20]. Interestingly, the occurence of skin irritation was low and similar between both groups. Given these results, adapalene might be favored above tretinoin.

A final retinoid I want to briefly cover is tazarotene (brand name Tazorac). It comes at a concentration ranging from 0.05 to 0.1 % and appears to be more effective than tretinoin [13, 21] and is reasonably well tolerated. It also seems superior to adapalene when both are combined with the antibiotic clindamycin [22]. Or at least it is on the short-term (the trial only ran for one month, which is relatively short). In a 16-week trial, in which both were used stand-alone, 0.1 % tazarotene appeared more effective than 0.3 % adapalene too, while being being nearly as well tolerated [23]. A different 12-week trial showed similar efficicacy of 0.1 % tazarotene compared to 0.3 % adapalene, but showed that adapelene was better tolerated [24]. The same was observed in another trial comparing 0.1 % adapalene with 0.1 % tazarotene [25]. So tazarotene might perhaps work a bit better than adapalene, but adapalene tends to be better tolerated. As such, adapalene seems to be a good choice when picking a retinoid.

Side-effects are similar to that of benzoyl peroxide (dry skin, redness of the skin, irritation of the skin, etcetera) and tazarotene seems to be the worse at that, then tretinoin and adapalene being the best tolerated. You could start off with 0.3 % adapalene once daily, applied to the affected areas in a thin layer. If side-effects seem too severe, you could switch to the lower concentration of 0.1 %. Keep in mind that side-effects tend to be the most severe at the start, waning off a bit the first couple of weeks. Similar to benzoyl peroxide, this does not always work very well against anabolic steroid-induced acne, but it is definitely worth a try (and preferably in combination with benzoyl peroxide or a short run of a topical antibiotic). And just as with benzoyl peroxide, it makes your skin more prone to sunburn, so to be sure to apply sunscreen appropriately on sunny days.

Antibiotics (topical)

Antibiotics, as you might expect, are mainly effective against the bacteria P. acnes. Typically used topical antibiotics are clindamycin and erythromycin. While the picture of the table earlier in this article notes that both of these have no effect on inflammation, they actually are anti-inflammatory (I'm not sure why the authors of the paper from which I got the table labeled it as having no effect on inflammation. The anti-inflammatory effect is not something controversial in the literature.) In fact, it is thought that it's primary mechanism of action is not so much it's bactericidal (killing bacteria) property, but it's anti-inflammatory effect [26]. The anti-inflammatory effect would be mediated via it's effect on bacteria though. Not so much by killing them, but by inhibiting some of their functions which would otherwise induce inflammation.

While also appropriate as a first-line treatment in most cases of acne, it should never be used stand-alone. The reason for this is simple: antibiotic resistance. A 10-year surveillance data study from the United Kingdom found antibiotic resistant P. acnes strains on 34.5 % of patients in 1991, and 55.5 % in 2000 [27]. A 2016 review writes that many countries report that more than 50 % of P. acnes strains are resistant to the commonly used topical antibiotics [12]. It is therefore very clear that antibiotic resistant strains are a problem and stand-alone antibiotics therapy should not be initiated. Not just because it wouldn't be that much effective anymore, but also because it further stimulates antibiotic resistant strains of P. acnes to pop up. The authors of the 2016 review therefore write: "Ideally, benzoyl peroxide in combination with a topical retinoid should be used instead of a topical antibiotic to minimise the impact of resistance.". If topical antibiotics were to be used, it's usage should be limited to short periods of time. Additionally, it should be combined with benzoyl peroxide (not only because it kills the bacteria too, limiting development of antibiotic resistant strains, but also because it enhances the effectiveness of the antibiotic itself).

If a topical antibiotic were to be chosen as part of a combination therapy, clindamycin should be the prefered option [28]. Tolerance is usually excellent.

Antibiotics (oral)

Largely the same rational as for topical antibiotics holds for oral antibiotics. They are effective against P. acnes and reduce inflammation. This includes antibiotics belonging to the tetracycline group (minocycline, doxycycline, tetracycline, lymecycline), macrolide group (erythromycin, azithromycin) and the antibiotic clindamycin. It is unclear whether one of these works better than the other, or if some duration or dosage should be preferred over another [29]. And yes, that also goes for minocycline. Despite it being widely assumed to be the most effective (and also the most prescribed), a Cochrane review concluded that there is no evidence that it is superior to other commonly used therapies [30].

So what remains is making a selection based on their side-effects profile. The tetracycline group can make your skin burn faster. So you'll need to watch out with the sun and apply sunscreen appropriately. Moreover, minocycline specifically has this nasty side-effect that it can cause skin pigmentation with prolonged usage [31]. Furthermore, it's reported that minocycline can cause staining of the teeth. Something which apparently seems to occur with about 3 -- 6 % of patients taking minocycline long-term at a dosage of more than 100 mg daily [32]. Tetracycline on the other hand has been occassionaly linked to something called idiopathic intracranial hypertension [33]. Which means as much as an increase of pressure around the brain (intracranial; within the skull) of unknown cause (idiopathic). It seems to be very rare and I'm just mentioning it because I stumbled upon it.

For the macrolide group there are some concerns that it might cause cardiac arrhythmia in a small number of patients, but all that fuzz seems overstated [34]. It's very unlikely to cause problems in otherwise healthy adults at all.

The main side-effect, which all of these oral antibiotics seem to have in common, is that of gastrointestinal (GI) problems (diarrhea, nauseau and sometimes even vomiting). Which isn't particularly useful for anabolic steroid users, since it's quite important to them to hit their nutrition intake goals.

Again, just like the topical antibiotics, this is something which might be a nice addition to benzoyl peroxide or retinoid therapy.

Isotretinoin (Roaccutane; Accutane [oral])

Isotretinoin (perhaps better known under it's brand names Accutane or Roaccutane) is the god of all acne treatments. It's hands-down the most effective treatment for acne. It actually belongs to the class of retinoids, albeit that you take this one orally instead of applying it to the skin.

As shown in the table earlier, it's effective at pretty much everything involved in the pathogenesis of acne. Most notably, it's extremely effective at inhibiting sebum production. Unfortunately, that's also causing a very dry skin, but I'll get to the side effects later (as this drug has quite some). This isn't particularly a first-line treatment (due to the side effects), except in cases of severe acne. Usually dermatologists resort to isotretinoin only when other therapies (the ones above) have failed. That is, it is prescribed to patients with severe acne or treatment-resistant acne. Because it is so extremely effective at inhibiting sebum production, it's also of great interest to anabolic steroid users. After all, the main change that triggers acne in anabolic steroid users is likely the androgen-induced increase in sebum production.

So how effective is it? In controlled trials, it shows a decrease in total lesion count ranging from 32 % to 93.3 % [35]. Now that 32 % looks a bit low, and it is. The reason for this is most likely the duration of that specific trial: 4 weeks. Isotretinoin simply works better and better with a higher cumulative dose. If you take a look at trials lasting 4 months or longer, the range goes from 69.8 % to 93.3 %. That's a lot better, right? And again, there's an interesting note about the study showing a decrease of 'only' 69.8 % in total lesion count [36]. The patients were given a really low dosage, namely 5 mg daily. To put that in perspective: normally a starting dosage of 0.5 mg/kg bw is used, which amounts to 40 mg daily for a 80 kg person. And mind you, to further put these numbers in perspective, in most trials the patients suffered from severe acne. So these numbers are nothing short of amazing.

What's interesting about the study with 5 mg daily is how effective it already was after 4 weeks. The subjects had low-grade adult acne with an average lesion count of about 10 at baseline. After only weeks 4 this roughly halved in the isotretinoin group, with a non-significant reduction in the placebo group. As the trial continued, this reduction in lesion count roughly continued, albeit at a slower pace.

Now I could go on and on about isotretinoins (roaccutanes) effectiveness against acne. Going into detail about these studies, but I don't think any of you reading this has any doubts about its effectiveness. It's amazingly effective. What's most interesting is its side effects. One thing your physician or dermatologist will let you take before you start with isotretinoin, is a blood test. After 1 month of treatment, the blood test is repeated, and then every 3 months again. The blood tests are done to assess your cholesterol, triglycerides, hemoglobin and markers of liver damage. The reason for this is that isotretinoin might increase cholesterol, triglycerides and markers of liver damage and decrease hemoglobin. The occurence of this is small though. A systematic review reported abnormal blood work in 4 % for those treated with isotretinoin and 0.1 % for those in the control groups [35]. And in the end, only 0.5 % of the patients treated with isotretinoin withdrew due to abnormal blood work (elevated liver enzymes).

The same review reported the numbers on a bunch of other adverse events which I'll iterate over. GI problems were reported in a low percentage of patients treated with isotretinoin. 2% of all reported adverse events by patients treated with isotretinoin were classified as GI problems. Interestingly, but not too unexpected, this percentage was actually higher in the control groups, namely 8.8 %. The reason I'm saying this is not too unexpected, is because in some studies the control groups took oral antibiotics. As noted previously, a main side-effect of oral antibiotics is GI problems.

7.2 % of the reported adverse effects with isotretinoin were ophthalmologic problems. What the heck are ophthalmologic problems you might ask. It's medical slang to describe stuff with your eyes. Think of having dry eyes, irritated eyes and conjunctivitis. Of note is that your eyes could get too dry for, or simply too easily irritated by, contact lenses. This could render you to be unable to wear them. There are some rarer ophthalmologic side-effects which I'm not going to cover. The interested reader could hit up the following reference: [37].

Peculiarly, isotretinoin usage is associated with psychiatric side-effects (4.3 % of the reported adverse events in the isotretinoin treated patients were psychiatric). The most common ones are simply fatigue or lethargy. Meh, boring.

I remember going through the isotretinoin leaflet years ago and it noted 'suicidial thoughts' and 'suicide' under the side-effects section. Less boring. Of course, it's hard to establish a causal relationship between isotretinoin usage and suicide, as it's relatively rare and it's likely that acne on its own plays a part in this. In fact, one study notes that severe acne is associated with an increased risk of attempted suicide [38]. And isotretinoin usage, at the population level, might even attenuate it. Simply because clearing the acne can help with that. Fat chance you'll feel better when your acne gets cleared. However, that is not to say that at the individual level, the risk might increase. As a final note on this, people with a history of attempted suicide may not need to be excluded from using isotretinoin according to the study I mentioned above (patients with a history of suicide attempts made new attempts to a lesser extent than patients who didn't have a history of it).

By far the most frequent reported adverse events are dermatological, with a whopping 65 % of all reported adverse events. There are some rare dermatological adverse events that might occur, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome. But most commonly it's just dry skin and all that comes about with it. Anf with dry skin I mean really dry skin. A lot of isotretinoin users use some kind of ointment or cream to make it bearable. Something like cetomacrogol cream would be handy by applying it several times per day on the dry parts, usually just the face. Also the lips can get very dry. So dry that the corners of the mouth can get inflamed (angular cheilitis). Applying petroleum jelly or vaseline-like ointments to the lips to counteract this is advisable. And, before I forget, your skin can get sunburnt real quick. So make sure to apply a high factor sunscreen when you go out in the sun. Additionally, a recent trial suggests that supplementation of omega-3 fatty acids might help against these side-effects [39]. The trial didn't describe particularly well what the dosage was, nor did they mention how much eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) it was. It seems to be 1 g of omega 3 fatty acids daily, but it could also be 1 g of fish oil daily.

As noted earlier, a regular starting dosage is 0.5 mg/kg bw. So if you're 80 kg, you start with 40 mg daily. This is then gradually build up towards 1 mg/kg bw, depending on how side-effects develop. Usage is traditionally stopped when a cumulative dosage of 120 -- 150 mg/kg bw is reached. It is thought that when this cumulative dosage is reached, the chance of relapse is very small. Although more recently it is proposed that it might be better to continue treatment till full clearance is reached, plus one additional month [40]. Now, this protocol of course is for people with 'regular' acne. Not acne developed because of the usage of anabolic steroids. In my experience, anabolic steroid users achieve good results with lower dosages and don't need to hit a certain cumulative dosage or use 0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg bw daily. Although this is likely not specific to steroid users, as noted earlier with the trial of Rademaker et al. demonstrating a firm reduction in lesion count in low grade acne after only 4 weeks at 5 mg daily [36]. Nevertheless, the chance for relapse is a bit higher with such low dosages. But this seems somewhat irrelevant for anabolic steroid users, as you'll remove the trigger for acne after going off. The acne usually disappears within a few weeks after cessation of AAS usage. As such, isotretinoin is commonly only used during steroid usage. Dosages as low as 10 to 20 mg every other day seem effective in this regard. On dosages like this, some don't notice any side-effects or just moderate drying of the skin and lips. A small percentage of people do seem to have some persistent acne even still after steroid usage, but good data on this is lacking.

Zinc (oral)

Zinc is a mineral that functions as a cofactor for a wide range of proteins in the body. And, apparently, it might aid in the treatment of acne. This was first noticed by Fitzherbert and Michaelsson et al. in the 1970s [41, 42]. Giving zinc-deficient patients some zinc improved their acne. Michaelsson et al. were so kind to conduct a double-blind study assessing the effectiveness of zinc supplementation compared to that of oxytetracycline (an antibiotic). The zinc group received zinc sulphate corresponding to 45 mg of elemental zinc daily. They found no difference between the groups and the average decrease in the acne score was about 70 % in both groups. Promising results I'd say: zinc similarly effective as an antibiotic. To put that dosage in perspective: the Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA) established by the U.S. Institute of Medicine (IOM) has been set at 8 and 11 mg daily for women and men, respectively. The Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) has been set at 40 mg daily. So they didn't even use a sickening dosage of zinc, just slightly above the UL.

Several mechanisms have been proposed for its efficacy in acne, although the exact mechanism is far from understood. It is thought that zinc might inhibit P acnes activity, modulate inflammation and suppress sebum excretion [43]. The decreased sebum excretion has been demonstrated in humans with topical zinc application (in combination with erythromycin) [44], so it's unsure if this also goes for orally administered zinc. Either way, it's currently unknown which mechanism plays the most important role in its efficacy.

A recent review lists 11 studies in which zinc was used as monotherapy for treatment of acne [45]. Of these 11 studies, 8 had a placebo group [46-53]. I'll focus on these 8 studies for the rest of this section, as they form the highest quality of evidence.

One study used zinc gluconate [47], while the others used zinc sulfate. Doses ranged from 100 mg zinc gluconate daily (14 mg elemental zinc) to 600 mg zinc sulfate daily (136 mg elemental zinc). Half of these studies found a significant objective improvement in acne compared to the placebo group [47, 48, 50, 52], whereas the other half didn't [46, 49, 51, 53]. Notably, one of these studies which didn't find a significant improvement compared to control in objective measurements, did find a superior improvement in physicians and patients subjective opinion [49]. Glancing over the dosages, I don't think these are to blame for the different findings between studies. Same goes for the duration of the studies, these were similar between the positive and negative studies. What I think is to blame is the moderate effect size of oral zinc therapy and the wide variation in acne improvements between subjects. The latter making it more difficult to find a statistical significant difference without a (very) large sample size. Especially in the light of the moderate effect size as I said. Additionally, it has been suggested that zinc is more effective in severe acne than mild to moderate acne [43].

The lowest effective dosage in one of the 4 positive trials was 100 mg zinc gluconate daily, equaling 14 mg elemental zinc. The other 3 positive studies used dosages of 200 mg, 300 and 600 mg zinc sulfate, equaling 45, 68 and 136 mg of elemental zinc. I suppose a dosage around 40 mg elemental zinc will be just fine for most. Higher comes with some side-effects, GI side-effects in particular. Nausea and even vomiting have also been reported, which seems to occur in a small number of people.

If you plan on dosing higher than that, it would be wise to supplement some copper too. The UL of 40 mg daily established by the Institute of Medicine was based on zincs ability to inhibit copper absorption [54]. If you tolerate it, I think zinc would be good to add to nearly any other acne treatment listed in this post.

5α-Reductase inhibitors (oral)

This is a type of drugs that belongs to the class of antiandrogen treatments. Anyways, so before I continue, I need to cover a tiny bit of biochemistry. Testosterone is converted to the more potent androgen dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in various tissues. More specifically, it’s converted by the action of an enzyme named 5α-reductase. This enzyme lends it name to the chemical reaction it catalyzes. It reduces testosterone on its fifth carbon atom, by adding an α-oriented hydrogen atom. That’s it, nothing more, nothing less. DHT is testosterone with an extra hydrogen atom at a certain position. The result of this is that it binds and activates the androgen receptor more strongly. The effect of testosterone is thus amplified in tissues which express 5α-reductase.

You will find this enzyme in a lot of tissues, like the prostate, scalp, liver and skin. More specifically, the sebocytes also express the enzyme. Now, another thing about this, is that this enzyme comes in a few different 'shapes'. There are 3 known 5α-reductase isozymes. That is, three different 'types' that catalyze the same reaction. This is important, because one tissue might express a different 5α-reductase isozyme than another, and certain drugs are isozyme-specific.

If we take a look at finasteride, it’s potent at inhibiting type II and type III 5α-reductase and is a lot less potent at inhibiting type I 5α-reductase [55]. So which ones are expressed in the sebaceous gland? Type I is richly expressed in it and type II is undetectable [56]. Type III also seems expressed in a human sebaceous gland cell line [57]. So finasteride appears a bad choice in this regard, as it’s relatively weak at inhibiting type I 5α-reductase. Indeed, a study demonstrated that 14 days of finasteride administration at 5 mg daily lowered sebum DHT concentration (a perfectly fine surrogate for its concentration in the sebaceous gland) by only 14.9 % [58]. Yet it strongly decreased serum DHT concentration (-65.8 %), highlighting it’s effectiveness at this dosage. Apparently the type III expression is of minor importance for sebaceous gland DHT production in light of these results.

So what about a type I inhibitor? The same trial with finasteride also experimented with the selective type I inhibitor MK-386. It demonstrated a decrease in sebum DHT concentration of 30.1 % and 49.1 % at 20 and 50 mg daily, respectively. That’s more like it.

But does this actually work against AV? Unfortunately, the answer is no [59]. A well-designed 3-month randomized placebo-controlled trial (n = 182) compared the effect of the selective type I inhibitor (25 mg daily) to an antibiotic (minocycline, a standard treatment for AV) and a placebo. Additionally, they also evaluated whether the combination of minocycline with the type I inhibitor worked better. The type I inhibitor worked as well as the placebo (P = 0.862) and the combination therapy did not work better than minocycline alone (P = 0.23).

I would also like to note that there has been a large (n = 106) randomized placebo-controlled trial with the usage of finasteride for the treatment of severe AV, but the results have never been published (NCT02502669). Given the small effect on sebum DHT concentration of an earlier study and given that the study was sponsored by Elorac Pharmaceuticals, it is likely the study hasn’t been published because it simply had no effect. (What other reason would a pharmaceutical company have to not publish the results if their drug actually worked? Right.)

Additionaly, a randomized-controlled trial found no difference in sebum production of the forehead, nose and back when dutasteride (an inhibitor of type I, II and III 5α-reductase) was added to varying doses of testosterone (25 mg up to 600 mg testosterone enanthate weekly) [60].

Concluding, there is no evidence to support the usage of 5α-reductase inhibitors for the treatment of acne. As such, I won't bother with covering potential side-effects of this class of drugs here.

Vitamin D (oral)

Vitamin D can be synthesized by the human body when the skin is exposed to UV radiation. It also is available from the diet, although there aren't really significant amounts of it in most foods. An exception is oily fish, such as salmon, mackerel and herring [61]. A 100 g serving of these fish give about 400 to 500 IU of vitamin D (1 IU of vitamin D is 0.025 mcg. And 1 mcg of vitamin D is thus 40 IU.). Additionally, sun-dried mushrooms, cod liver oil and oils from other fish could also provide some vitamin D. Moreover, some countries fortify certain foods with vitamin D. It's not uncommon to see vitamin D-fortified milk and in my country (the Netherlands) some baking and frying products are fortified with vitamin D (300 IU per 100 g). However, most people don't eat fish that frequently and as it turns out, the primary dietary source of vitamin D among Dutch people are baking and frying products and meat, instead of fish [62]. Needless to say, that altogether, dietary vitamin D-intake is usually quite low and insufficient to meet vitamin D requirements when not exposed to sufficient sunlight.

Indeed, vitamin D deficiency is quite prevalent. As the renowned vitamin D researcher Michael Holick writes: "Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency is a global health issue that afflicts more than one billion children and adults worldwide." [63]. And this includes athletes. A recent Dutch study found that about two thirds of a sample of 128 highly trained athletes was either vitamin D deficient (<50 nmol/L 25(OH)D) or insufficient (<75 nmol/L 25(OH)D).

So, what does any of this have to do with acne? So, a case-control study found that vitamin D deficiency (defined as <30 nmol/L in this paper) was a lot more common in patients with acne (48.8 %) than in healthy controls (22.5 %) [64]. Moreover, they also found a correlation between the severity of acne and the 25(OH)D concentration. The more severe the acne, the lower the 25(OH)D concentration. And more specifically, a correlation between the inflammatory lesion count and the 25(OH)D concentration (there was not a significant correlation with non-inflammatory lesion count). Subsequently, these researchers were so kind to not just publish these results as is. Because it leaves a big question mark: is it causal or correlative? Instead, these researchers started a randomized-controlled trial with the ones who were vitamin D deficient. A total of 39 vitamine D-deficient patients with acne were randomized to either receiving 1000 IU vitamin D daily or a placebo. After 8 weeks of treatment there was a significant decrease in inflammatory lesions in the vitamin D group compared with the placebo group.

As such, it seems that vitamin D supplementation can be beneficial to reduce the number of inflammatory leasions in vitamin D-deficient acne patients. However, the dosage used in this stody (1000 IU daily) is likely to be too low for most to achieve adequate vitamin D levels. In this study, the 25(OH)D concentration rised from around 20 nmol/L to around 40 nmol/L after 8 weeks. That's a concentration which is still deemed deficient (<50 nmol/L) by the Endocrine Society (above 75 nmol/L would be deemed adequate) [65]. So you're likely better of supplementing a higher dosage. Nevertheless, it's unsure whether this would improve acne more than in this study.

Safety-wise a lot of studies are available in the literature. Quite some review papers have been dedicated to this subject (I cannot be bothered to cite them here). Too much vitamin D can lead to problems, which primarily result from the hypercalcemia (too high serum calcium) and hyperphosphatemia (too high serum phosphate) that can occur with vitamin D supplementation. This can lead to headaches, nauseau, throwing up, diarrhea, weight loss, polyuria and polydipsia. On the long term soft tissue calcification can occur, including calcification of the blood vessel lining. Either way, all these side effects are thought to occur because of overactive vitamin D signaling [66].

The serum 25(OH)D concentration that can be reached by sun light exposure lies around 100 -- 150 nmol/L [67, 68]. Given that vitamin D toxicity due to sunlight exposure has never been reported, one could argue that this is a safe serum concentration. Indeed, the serum 25(OH)D concentration at which hypercalcemia develops is unsure, but is estimated to be around 375 -- 500 nmol/L -- a concentration which needs to be maintained for a prolonged period of time too [66]. Such values have only been reported in the literature with involuntarily overdosing. The dosage required to obtain a concentration above 100 nmol/L appears to be around 4000 IU daily [67, 69], assuming a low concentration is present when starting supplementation. Of course, in those who already have a concentration above 100 nmol/L, supplementation will lead to a further increase.

A risk analysis by Hathcock et al. puts the highest dosage at which no adverse effects occur (NOAEL, no-observed-adverse-effect level) at 10000 IU vitamin D3 daily [70]. The — conservative — European Food and Safety Authority has put the tolerable upper limit of intake at 4000 IU daily [71].

Omega-3 and γ-linolenic acid (GLA; oral)

Just when I thought I was done with this article on acne, I stumbled upon this RCT in which participants received omega-3 fatty acids, γ-linolenic acid (GLA) or a placebo [72]. I first wanted to discard this study because they couldn't get the fatty acid right in the abstract (they're writing about γ-linoleic acid instead of γ-linolenic acid). Which tends to be a sign of just general sloppiness. But ok, I decided to read it anyways as it was published in a reputable journal for this niche (Acta Dermato-Venereologica). And indeed, the trial itself was setup quite ok.

As said, there were three intervention groups. The omega-3 group received 1 g of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and 1 g of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) daily. The GLA group received 2 g of borage oil daily, which provided 400 mg of GLA. And the placebo group received a placebo, obviously. The treatment lasted a total of 10 weeks and a total of 45 subjects participated. The subjects had mild to moderate acne and all the subjects completed the study.

After the 10 weeks, the omega-3 and GLA groups showed some good improvement in their acne. The inflammatory lesion count was significantly reduced from 10.1 to 5.8 in the omega-3 group and from 9.8 to 6.6 in the GLA group. The placebo group demonstrated no change (from 9.9 to 10.2). The non-inflammatory lesion count also significantly dropped in the omega-3 and GLA groups (from 23.5 to 18.9 and 22.8 to 19.2, respectively). Again, this remained unchanged in the placebo group. To highlight: these changes in the omega-3 and GLA groups were also sigificant compared to the placebo group. Finally, the acne severity significantly decreased in both these groups compared to the placebo group. No severe adverse effects were reported, but two patients in the omega-3 group and one in the GLA group reported mild gastrointestinal discomfort, and one patient in the omega-3 group reportd temporary diarrhoea.

To date this seems to be the only RCT in which fatty acid supplementation is used as a treatment for acne. It would be interesting to see in how much this also works with severe acne and whether the results of this study are replicable at all. And on top of that, it would be interesting to see if there's some kind of dose-response relationship, as in; would dosing higher work even better? And what if you combine the omega-3 and GLA: is their effectiveness additive? Either way, given the wide availability and ease of use of these fatty acids and their established safety profile, it seems to be a nice addition in the arsenal for acne treatment.

References

- B. Dreno and F. Poli. Epidemiology of acne. Dermatology, 206(1):7–10, 2003.

- D. Thiboutot, H. Gollnick, V. Bettoli, B. Dréno, S. Kang, J. J. Leyden, A. R. Shalita, V. T. Lozada, D. Berson, A. Finlay, et al. New insights into the management of acne: an update from the global alliance to improve outcomes in acne group. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 60(5):S1–S50, 2009.

- A. H. Jeremy, D. B. Holland, S. G. Roberts, K. F. Thomson, and W. J. Cunliffe. Inflammatory events are involved in acne lesion initiation. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 121(1):20–27, 2003.

- B. R. Vowels, S. Yang, and J. J. Leyden. Induction of proinflammatory cytokines by a soluble factor of propionibacterium acnes: implications for chronic inflammatory acne. Infection and immunity, 63(8):3158–3165, 1995.

- J. Imperato-McGinley, T. Gautier, L. Cai, B. Yee, J. Epstein, and P. Pochi. The androgen control of sebum production. studies of subjects with dihydrotestosterone deficiency and complete androgen insensitivity. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 76(2):524–528, 1993.

- P. E. Pochi and J. S. Strauss. Sebaceous gland response in man to the administration of testosterone, d4-androstenedione, and dehydroisoandrosterone. J Invest Dermatol, 52:32–36, 1969.

- S. Bhasin, T. G. Travison, T. W. Storer, K. Lakshman, M. Kaushik, N. A. Mazer, A.-H. Ngyuen, M. N. Davda, H. Jara, A. Aakil, et al. Effect of testosterone supplementation with and without a dual 5areductase inhibitor on fat-free mass in men with suppressed testosterone production: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 307(9):931–939, 2012.

- J. M. Choi, V. K. Lew, and A. B. Kimball. A single-blinded, randomized, controlled clinical trial evaluating the effect of face washing on acne vulgaris. Pediatric dermatology, 23(5):421–427, 2006.

- W. E. Pace. A benzoyl peroxide-sulfur cream for acne vulgaris. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 93(6):252, 1965.

- J. Waller, F. Dreher, S. Behnam, C. Ford, C. Lee, T. Tiet, G. Weinstein, and H. Maibach. ‘keratolytic’properties of benzoyl peroxide and retinoic acid resemble salicylic acid in man. Skin pharmacology and physiology, 19(5):283–289, 2006 N. H. Mohd Nor and Z. Aziz. A systematic review of benzoyl peroxide for acne vulgaris. Journal of Dermatological Treatment, 24(5):377–386, 2013.

- M. Ozolins, E. A. Eady, A. J. Avery, W. J. Cunliffe, A. L. W. Po, C. O’Neill, N. B. Simpson, C. E. Walters, E. Carnegie, J. B. Lewis, et al. Comparison of five antimicrobial regimens for treatment of mild to moderate inflammatory facial acne vulgaris in the community: randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 364(9452):2188–2195, 2004.

- T. R. Walsh, J. Efthimiou, and B. Dréno. Systematic review of antibiotic resistance in acne: an increasing topical and oral threat. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 16(3):e23–e33, 2016.

- J. Leyden, E. Tanghetti, B. Miller, M. Ung, D. Berson, and J. Lee. Once-daily tazarotene 0.1% gel versus once-daily tretinoin 0.1% microsponge gel for the treatment of facial acne vulgaris: a double-blind randomized trial. Cutis, 69(2 Suppl):12–19, 2002.

- A. J. Brandstetter and H. I. Maibach. Topical dose justification: benzoyl peroxide concentrations. Journal of Dermatological Treatment, 24(4):275–277, 2013.

- G. Stüttgen. Historical perspectives of tretinoin. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 15(4):735–740, 1986.

- A. Thielitz and H. Gollnick. Topical retinoids in acne vulgaris. American journal of clinical dermatology, 9(6):369–381, 2008.

- R. Berger, R. Rizer, A. Barba, D. Wilson, D. Stewart, R. Grossman, M. Nighland, and J. Weiss. Tretinoin gel microspheres 0.04% versus 0.1% in adolescents and adults with mild to moderate acne vulgaris: a 12-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, phase iv trial. Clinical therapeutics, 29(6):1086–1097, 2007.

- G. F. Webster. Topical tretinoin in acne therapy. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 39(2):S38–S44, 1998.

- W. Cunliffe, M. Poncet, C. Loesche, and M. Verschoore. A comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of adapalene 0.1% gel versus tretinoin 0.025% gel in patients with acne vulgaris: a meta-analysis of five randomized trials., 1998.

- D. Thiboutot, D. M. Pariser, N. Egan, J. Flores, J. H. Herndon Jr, N. B. Kanof, S. E. Kempers, S. Maddin, Y. P. Poulin, D. C. Wilson, et al. Adapalene gel 0.3% for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled, phase iii trial. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 54(2):242–250, 2006.

- G. Webster, D. Berson, L. Stein, D. Fivenson, E. Tanghetti, and M. Ling. Efficacy and tolerability of once-daily tazarotene 0.1% gel versus once-daily tretinoin 0.025% gel in the treatment of facial acne vulgaris: a randomized trial. Cutis, 67(6 Suppl):4–9, 2001.

- R. Maiti, C. S. Sirka, M. A. Rahman, A. Srinivasan, S. Parida, and D. Hota. Efficacy and safety of tazarotene 0.1% plus clindamycin 1% gel versus adapalene 0.1% plus clindamycin 1% gel in facial acne vulgaris: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. Clinical drug investigation, 37(11):1083–1091, 2017.

- E. Tanghetti, S. Dhawan, L. Green, J. R. Del, Z. Draelos, J. Leyden, A. Shalita, D. A. Glaser, P. Grimes, G. Webster, et al. Randomized comparison of the safety and efficacy of tazarotene 0.1% cream and adapalene 0.3% gel in the treatment of patients with at least moderate facial acne vulgaris. Journal of drugs in dermatology: JDD, 9(5):549–558, 2010.

- D. Thiboutot, S. Arsonnaud, and P. Soto. Efficacy and tolerability of adapalene 0.3% gel compared to tazarotene 0.1% gel in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Journal of drugs in dermatology: JDD, 7(6Suppl):s3–10, 2008.

- D. Pariser, L. E. Colón, L. A. Johnson, and R. W. Gottschalk. Adapalene 0.1% gel compared to tazarotene 0.1% cream in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Journal of drugs in dermatology: JDD, 7(6 Suppl):s18–23, 2008.

- M. Toyoda and M. Morohashi. An overview of topical antibiotics for acne treatment. Dermatology, 196(1):130–134, 1998.

- P. Coates, S. Vyakrnam, E. Eady, C. Jones, J. Cove, and W. Cunliffe. Prevalence of antibiotic-resistant propionibacteria on the skin of acne patients: 10-year surveillance data and snapshot distribution study. British Journal of Dermatology, 146(5):840–848, 2002.

- A. L. Zaenglein, A. L. Pathy, B. J. Schlosser, A. Alikhan, H. E. Baldwin, D. S. Berson, W. P. Bowe, E. M. Graber, J. C. Harper, S. Kang, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 74(5):945–973, 2016.

- A. Bienenfeld, A. R. Nagler, and S. J. Orlow. Oral antibacterial therapy for acne vulgaris: an evidencebased review. American journal of clinical dermatology, 18(4):469–490, 2017.

- E. A. B. C. N. J. T. K. Garner, SE and C. Popescu. Minocycline for acne vulgaris: efficacy and safety. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1(8), 2012.

- A. N Geria, A. L Tajirian, G. Kihiczak, and R. A Schwartz. Minocycline-induced skin pigmentation: an update. Acta ermatovenerologica Croatica, 17(2):0–0, 2009.

- M. Good and D. Hussey. Minocycline: stain devil? British Journal of Dermatology, 149(2):237–239, 2003.

- K. Gardner, T. Cox, and K. B. Digre. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension associated with tetracycline use in fraternal twins case reports and review. Neurology, 45(1):6–10, 1995.

- R. K. Albert, J. L. Schuller, and C. C. R. Network. Macrolide antibiotics and the risk of cardiac arrhythmias. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 189(10):1173–1180, 2014.

- I. Vallerand, R. Lewinson, M. Farris, C. Sibley, M. Ramien, A. Bulloch, and S. Patten. Efficacy and adverse events of oral isotretinoin for acne: a systematic review. British Journal of Dermatology, 178(1):76–85, 2018.

- M. Rademaker, J. Wishart, and N. Birchall. Isotretinoin 5 mg daily for low-grade adult acne vulgaris–a placebo-controlled, randomized double-blind study. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 28(6):747–754, 2014.

- F. Fraunfelder, F. Fraunfelder, and R. Edwards. Ocular side effects possibly associated with isotretinoin usage. American journal of ophthalmology, 132(3):299–305, 2001.

- A. Sundström, L. Alfredsson, G. Sjölin-Forsberg, B. Gerdén, U. Bergman, and J. Jokinen. Association of suicide attempts with acne and treatment with isotretinoin: retrospective swedish cohort study. Bmj, 341:c5812, 2010.

- M. Mirnezami and H. Rahimi. Is oral omega-3 effective in reducing mucocutaneous side effects of isotretinoin in patients with acne vulgaris? Dermatology research and practice, 2018, 2018.

- D. M. Thiboutot, B. Dréno, A. Abanmi, A. F. Alexis, E. Araviiskaia, M. I. B. Cabal, V. Bettoli, F. Casintahan, S. Chow, A. da Costa, et al. Practical management of acne for clinicians: An international consensus from the global alliance to improve outcomes in acne. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 78(2):S1–S23, 2018.

- J. Fitzherbert. Zinc deficiency in acne vulgaris. The Medical journal of Australia, 2(20):685–686, 1977.

- G. Michaëlsson, L. Juhlin, and K. Ljunghall. A double-blind study of the effect of zinc and oxytetracycline in acne vulgaris. British Journal of Dermatology, 97(5):561–566, 1977.

- Y. S. Bae, N. D. Hill, Y. Bibi, J. Dreiher, and A. D. Cohen. Innovative uses for zinc in dermatology. Dermatologic clinics, 28(3):587–597, 2010.

- C. Piérard-Franchimont, V. Goffin, G. Piérard, J. Visser, and H. Jacoby. A double-blind controlled evaluation of the sebosuppressive activity of topical erythromycin-zinc complex. European journal of clinical pharmacology, 49(1-2):57–60, 1995.

- J. Cervantes, A. E. Eber, M. Perper, V. M. Nascimento, K. Nouri, and J. E. Keri. The role of zinc in the treatment of acne: A review of the literature. Dermatologic therapy, 31(1):e12576, 2018.

- K. Weismann, S. Wadskov, and J. Sondergaard. Oral zinc sulphate therapy for acne vulgaris. Acta dermato-venereologica, 57(4):357–360, 1977.

- B. Dreno, P. Amblard, P. Agache, S. Sirot, and P. Litoux. Low doses of zinc gluconate for inflammatory acne. Acta Derm Venereol, 69(6):541–3, 1989.

- K. Göransson, S. Liden, and L. Odsell. Oral zinc in acne vulgaris: a clinical and methodological study. Acta dermato-venereologica, 58(5):443–448, 1978.

- L. Hillström, L. Pettersson, L. Hellbe, A. Kjellin, C.-g. Leczinsky, and C. Nordwall. Comparison of oral treatment with zinc sulphate and placebo in acne vulgaris. British Journal of Dermatology, 97(6):679–684, 1977.

- S. Liden, K. Göransson, and L. Odsell. Clinical evaluation in acne. Acta dermato-venereologica. Supplementum, pages 47–52, 1980.

- L. Orris, A. R. Shalita, D. Sibulkin, S. London, and E. H. Gans. Oral zinc therapy of acne: absorption and clinical effect. Archives of dermatology, 114(7):1018–1020, 1978.

- K. Verma, A. Saini, and S. Dhamija. Oral zinc sulphate therapy in acne vulgaris: a double-blind trial. Acta dermato-venereologica, 60(4):337–340, 1980.

- V. M. Weimar, S. C. Puhl, W. H. Smith, et al. Zinc sulfate in acne vulgaris. Archives of dermatology, 114(12):1776–1778, 1978.

- I. Copper. Dietary reference intakes for vitamin A vitamin K, arsenic, boron, chromium, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, silicon, vanadium, and zinc. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2001.

- K. Yamana, F. Labrie, et al. Human type 3 5a-reductase is expressed in peripheral tissues at higher levels than types 1 and 2 and its activity is potently inhibited by finasteride and dutasteride. Hormone molecular biology and clinical investigation, 2(3):293–299, 2010.

- F. Azzouni, A. Godoy, Y. Li, and J. Mohler. The 5 alpha-reductase isozyme family: a review of basic biology and their role in human diseases. Advances in urology, 2012, 2012.

- M. Samson, F. Labrie, C. C. Zouboulis, et al. Biosynthesis of dihydrotestosterone by a pathway that does not require testosterone as an intermediate in the sz95 sebaceous gland cell line. The Journal of investigative dermatology, 130(2):602–604, 2010.

- J. I. Schwartz, W. K. Tanaka, D. Z. Wang, D. L. Ebel, L. A. Geissler, A. Dallob, B. Hafkin, and B. J. Gertz. Mk-386, an inhibitor of 5a-reductase type 1, reduces dihydrotestosterone concentrations in serum and sebum without affecting dihydrotestosterone concentrations in semen. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 82(5):1373–1377, 1997.

- J. Leyden, W. Bergfeld, L. Drake, F. Dunlap, M. P. Goldman, A. B. Gottlieb, M. P. Heffernan, J. G. Hickman, M. Hordinsky, M. Jarrett, et al. A systemic type i 5 a-reductase inhibitor is ineffective in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 50(3):443–447, 2004.

- S. Bhasin, T. G. Travison, T. W. Storer, K. Lakshman, M. Kaushik, N. A. Mazer, A.-H. Ngyuen, M. N. Davda, H. Jara, A. Aakil, et al. Effect of testosterone supplementation with and without a dual 5areductase inhibitor on fat-free mass in men with suppressed testosterone production: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 307(9):931–939, 2012.

- M. F. Holick. Vitamin d in health and disease: Vitamin d for health and in chronic kidney disease. In Seminars in dialysis, volume 18, pages 266–275. Wiley Online Library, 2005.

- C. T. van Rossum, H. P. Fransen, J. Verkaik-Kloosterman, E. J. Buurma-Rethans, and M. C. Ocke. Dutch national food consumption survey 2007-2010: Diet of children and adults aged 7 to 69 years. 2011

- M. F. Holick. The vitamin d deficiency pandemic: approaches for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, 18(2):153–165, 2017.

- S.-K. Lim, J.-M. Ha, Y.-H. Lee, Y. Lee, Y.-J. Seo, C.-D. Kim, J.-H. Lee, and M. Im. Comparison of vitamin d levels in patients with and without acne: a case-control study combined with a randomized controlled trial. PloS one, 11(8):e0161162, 2016.

- M. F. Holick, N. C. Binkley, H. A. Bischoff-Ferrari, C. M. Gordon, D. A. Hanley, R. P. Heaney, M. H. Murad, and C. M. Weaver. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin d deficiency: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 96(7):1911–1930, 2011.

- G. Jones. Pharmacokinetics of vitamin d toxicity. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 88(2):582S–586S, 2008.

- R. Vieth. Vitamin d supplementation, 25-hydroxyvitamin d concentrations, and safety. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 69(5):842–856, 1999.

- M. J. Barger-Lux and R. P. Heaney. Effects of above average summer sun exposure on serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d and calcium absorption. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 87(11):4952–4956, 2002.

- R. Vieth, P.-C. R. Chan, and G. D. MacFarlane. Efficacy and safety of vitamin d3 intake exceeding the lowest observed adverse effect level. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 73(2):288–294, 2001.

- J. N. Hathcock, A. Shao, R. Vieth, and R. Heaney. Risk assessment for vitamin d. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 85(1):6–18, 2007.

- N. EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products and A. (NDA). Scientific opinion on the tolerable upper intake level of vitamin d. EFSA Journal, 10(7):2813, 2012.

- J. Y. Jung, H. H. Kwon, J. S. Hong, J. Y. Yoon, M. S. Park, M. Y. Jang, and D. H. Suh. Effect of dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acid and gamma-linolenic acid on acne vulgaris: a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Acta dermato-venereologica, 94(5):521–526, 2014.